Last week I had a first. A teacher returned a book from my classroom library that a 9th grade student had borrowed the day before. Apparently the teacher caught the student reading it in math class and confiscated it.

Although I in no way condone reading novels in math class (I confiscate my own fair share of prohibited items in an average work day), I can’t deny that I was excited that, for at least one of my students, reading has become an addiction. As a lover of reading, I place a very high value on reading and believe that one of the most important ways a teacher can influence his or her students in terms of long term educational success is to instill in them a love of reading.

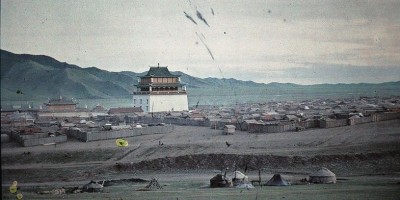

Mongolians have a tradition of greatly valuing books and respecting literature, poetry, and erudition. Unfortunately, this respect seems at times to put reading on too high a pedestal and perversely manifests itself in the educational system in the form of programs or curricula that discourage the idea of reading as a fun or leisurely educational activity. Kindergarten and elementary school teachers in practice do not read out loud to their students, and although there is class time mandated for guided student reading, the book selection in classes is limited and carefully chosen, in my opinion, to bore even dedicated readers like myself. Our school has a library with several hundred books, but it is sadly under utilized. It is rarely ever open, it is housed in a very cold room in an old building next to the school, and it primarily consists of moldy books in Russian or equally impenetrable tomes in English dedicated to topics such as graduate level biochemistry that were donated by well-meaning but misguided international aid organizations.

Books as a conversation starter

Interesting books that teachers do keep in their rooms are often viewed as status symbols and are kept behind glass doors or in locked cabinets to keep them safe from the wear and tear of students’ hands. Yet even if teachers do wish to supply their students with books, they are expensive making it difficult for teachers to assign entire classes the same book to read.

Perhaps the most disturbing issue of all, though, is some teachers’ attitudes or misunderstandings about reading which are not challenged by a professional culture that recognizes the importance of making reading an enjoyable activity from a young age. With a grant from a non-profit organization called Friends of Mongolia and donations from family members and friends, I have been able to build a collection of over 150 Mongolian language novels, comic, history, adventure, and reference books in my classroom. I may be an English teacher, but I am pragmatic enough to recognize that no student is going to try to read a book in a foreign language until they enjoy reading in their native language. Therefore, in addition to teaching English, I act as a part time librarian checking out 30-40 books a day. My bookshelves may be constantly disorganized and the books may need to be taped back together regularly due to wear and tear, but seeing how excited kids get when they find a coveted copy of “Super Friends: Dinosaur City” on the shelves makes it worthwhile. My library patrons are in grades 2 to 11 and include boys and girls, “good students” and “bad”, and an ever increasing number of serial readers who can be spotted walking through the halls absorbed in a book.

Reading as a time for self-learning

Returning to the issue of misguided perceptions of teachers, it can be summed up by explaining why I don’t lend first graders books. Why not, you ask? Aren’t they also in need of being exposed to colorful, engrossing, and fun books? Well, I don’t give books to first graders because I was told by their teacher, “Don’t give them any books because they can’t read yet.” I am still stunned by that request. Research shows that “as students become engaged readers, they provide themselves with self-generated learning opportunities that are equivalent to several years of education.”1 Additionally, other studies show that children who are read to as young children (i.e. exposed to books and the written word before they can read), have higher vocabulary rates than children of the same age who were not read to.2 Children need exposure to books well before they can read so they can learn the very basics of handling books, turning pages, holding conversations about pictures, and last but not least learning how to read. Not giving books to children who can’t read yet is like not speaking to a child because they can’t speak yet. As Jacqueline Kennedy once said “There are many little ways to enlarge your child’s world. Love of books is the best of all.” I just take for granted that a teacher should encourage the act of reading in a child of any age, and I was surprised and disappointed to learn my colleague had a different perspective.

Each time our school director presents another laptop or a wide screen television to a teacher in our school as part of a government or international aid-organization sponsored program, I appreciate the intent behind these improvements to the school’s available equipment (even though we rarely have electricity during the school day), but I would love to see those in charge of the school system and their international partners actually take a step or two back and focus on supplying every teacher and classroom with educational and entertaining books and fostering a professional culture in which love of reading even in first graders is considered an essential quality of a first rate educational system. Not only are books and a reading culture proven ways to promote better educational outcomes but there is the added bonus that no electricity is required.

About the Author

Sarah (Sadie) Munson currently lives and works in Umnugobi Province as an English teacher. She holds a bachelors degree from the University of Montana and a Masters of Human Ecology from the University of Wisconsin. Her professional interests and experiences include primary and secondary education, child development and family education, and community development. She can be reached at sarahmunson@gmail.com.

Footnotes

1. Guthrie J.T. and Wigfield A., Engagement and Motivation in Reading, 2000. Cited in Reading For Pleasure, The Strategy and Communications Department of The National Union of Teachers, 2010.

2. Washbrook E. and Waldfogel J., Cognitive Gaps in Early Years, The Sutton Trust, 2010. Cited in Reading For Pleasure, The Strategy and Communications Department of The National Union of Teachers, 2010.